Five minutes after choosing Possibility as my word for January 2024, I had the most negative temper tantrum because everything felt impossible. The feeling began when I woke up and it was -9F (-22C), the dog refused to go out, Kurt was sick, my nerve pain had returned in my leg, and there was no milk in the house. I wrote 2025 in my journal, as if some part of me knew it was best to just skip 2024.

Then I remembered that I had signed up for a pottery class way back in 2023 when life was easy, and it started today. A small group of female friends and I were going to create a muse out of clay in three days under the brilliant guidance of Caroline Douglas. But today, the idea felt frivolous, indulgent, even crazy to spend three mornings doing Arts and Crafts while I was convinced we were going broke, I needed to get back to work after the holidays, and someone had to get groceries. But I went to the pottery class anyway, hoping for a little grace.

In the studio, I thought I would feel grounded, doing something with my hands. Instead I felt anxious, incompetent, and full of comparative, sulky energy. Even when Caroline set us up with beautiful molds for our muse’s face and showed us how to assemble the body, I still felt stuck.

My classmates were quietly creating masterpieces: a goddess with long flowing hair, a golden-crowned muse with protective evil eyes, a stunning woman with two faces and two moods, and Venus riding upright in a beautiful boat. While they gushed, “This is the most fun I’ve had in so long,” I worked my clay slab with the skill of a kindergartener and a lot less enthusiasm.

I had imagined that I would make a Gaia goddess, a sculpture I could put in the garden and bring offerings to in gratitude for Nature. Yet the clay was hardening, drying-up, and cracking because I remained stuck and indecisive, overwhelmed by the grandeur of my vision in relation to my diminutive skill.

Then I added a single leaf to my goddess’s waistline, and I felt better. I used Indian wooden blocks for the leaf pattern, and pressed lace and river stones into her skirt. I attached more leaves to make a belt. I liked what I was creating. But then one leaf fell off, then another.

I thought, I should start over. I didn’t say it out loud, but right on cue, I overheard Caroline say to someone else in the class, “Don’t ever start over, clay is forgiving. You can always repair what you’ve done. Repair. Repair.”

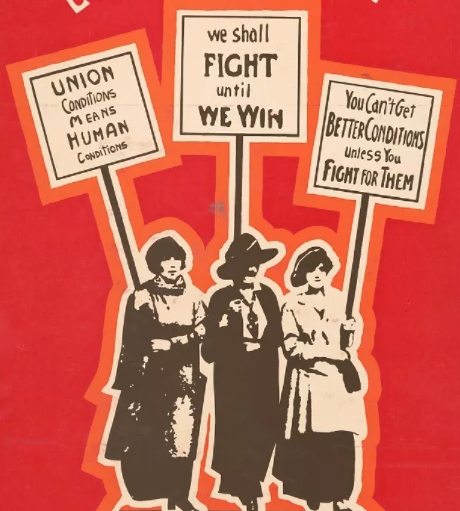

Repair: from late Latin repatriare: ‘return to one’s country.’ To put together what is torn. It turns out that to fix what is broken I needed to return to myself (or drive to Canada ;). The problem was not my lack of skill, it was that I was trying too hard to be like the others. I looked at the face of my muse and she seemed to whisper back, “You can’t get this wrong.”

On Day 2, I added elements that were deeply personal, like a backbone, as a kind of prayer and homage to my spine. We each have 33 vertebrae, creating the strongest bone in our body. My spinal column has just 26 vertebrae, with 6 fused and one removed, yet it is perfect. It is flexible and resilient. The source of my inner and outer strength. As I shaped her spine, I felt calm.

On Day 3, there were two problems. After days of freezing temperatures, the studio heat wasn’t working. It was so cold that Caroline suggested we cancel the class. Now, things had shifted enough inside me that nothing could keep me from the workshop. So we refused to cancel. Instead, everyone showed up and we worked in our parkas and hats, dancing to keep our toes warm. The second problem was that my muse’s leaves kept falling off.

Caroline walked over to where I was holding the torn and broken leaves and said, “Wet the slab, add more clay, crosshatch, and connect again.”

Connect again. Repair.

With Caroline’s experience and encouragement from the amazing women in the studio, I felt my way into my word for 2024, Possibility. Maybe I am healthy. Maybe Kurt will feel better soon. Maybe Hazel is picking up milk from the store right now. My sculpture is beautiful, maybe I am too. Maybe it will all work out. Just because I don’t know how, doesn’t mean that it isn’t possible.

Love,

Susie

- My Neurosurgeon called with good news! My scans look good – the nerve pain is likely caused by post-surgical scar tissue and inflammation on my spine. It may stick around for a long time, but I can manage it with meds and strength training. Yay!!

- It’s now 48 degrees F (9 Celsius) and sunny outside!