The Days of Awe are the ten days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Though I am not Jewish, they are an invitation to pause, make amends, and commit to transformation. Meanwhile, Canadian Thanksgiving celebrates the harvest, but it’s also an annual reminder to stop, turn back on the past year, note the mistakes and the losses, and acknowledge how things could have turned out much worse, but didn’t. It always made sense to me, to gather friends and family in October, to mark how far we’ve come and to give thanks for all that we have.

When we first moved to Boulder, CO, I stood in our elementary school playground at pick-up time on a windy day and invited our new friends over for Thanksgiving. Oh! They asked, “How is Canadian Thanksgiving different?” I told them the usual stuff: that it falls on the second Monday of October instead of the fourth Thursday in November. And that Canadians don’t have pilgrims, but instead take the day to be grateful that our cellars are full of squash and apples and potatoes. I also implied that it’s a little more relaxed in Canada. Some people have the meal on Sunday, others on Monday, and families can serve whatever they want. We usually have ham instead of turkey in our family, for example. The point isn’t what we eat or when, but that we pause to give thanks. There’s no rush to go shopping on “Black Friday” or “Cyber Monday”–it’s just a meal together, full of gratitude and grace.

“Oh,” they said. “We’d love to come!”

I blame it on the wind that day; it made me feel mischievous and bold, so I kept talking, spinning a tale that veered away from the truth. I said, “There’s a catch. The other difference is that Canadians have a superstitious streak. We eat in costumes to disguise ourselves from the bad spirits who might bring harm or give us an exceptionally cold winter. Back in the 1800s, people wore veils and hats and scarves, but now people dress up for fun: you know, eighties outfits and gorilla suits.”

“Alright, sure,” they responded without blinking, and I thought they knew I was joking. It didn’t occur to me to tell them that I had made the last part up.

The following Sunday, our guests arrived wearing afros and gold disco boots, banana suits and Harry Potter capes, carrying mashed potatoes and brussel sprouts. They seemed surprised that I wasn’t dressed up. But I was more surprised than they were; They had believed me! I couldn’t back down now. So I ran to the closet and found the dress-up bin and then my family piled into the bathroom and threw costumes on, while I explained what the heck was going on.

We ate that way, fake mustaches falling into the soup, mashed potatoes getting on the low-hanging disco sleeves, and we didn’t tell them the truth until after dinner and before the butter tarts were served. Our guests leaned back in astonishment, but they chose to keep their costumes on through dessert and all the way home. It’s now a tradition with those families–we dress up and have a meal together every October. Our intention in keeping this joke alive was never to mock the holiday, but to lighten it up a little. I thought, “Why can’t we be grateful and silly at the same time?” I also just like to wear costumes. They make me laugh.

The connection between Thanksgiving and the Days of Awe is this: For a moment each autumn, we stop and reflect. We remember that what makes us human is that we are capable of making great mistakes, and yet we are also capable of great transformation. Some say that Rosh Hashanah celebrates the creation of the world. But if you believe that creation is ongoing, then you celebrate that you have a hand in how it plays out by repairing broken relationships and giving thanks for the ones that are whole and holy. You also take part in creation by making choices every day. On Yom Kippur, observant Jews blow the ancient ram’s horn to wake everyone up and ask, Are you the person you want to be?

During the Days of Awe, I am hungry to be outside in nature as much as possible. It’s there that I do my best reflecting. And though I love gathering family and friends close to dress up and feast and laugh, I also know that I have to be alone, because transformation starts with the self. I walk under trees and ask myself, What are you grateful for? How are you talking to your loved ones? What do you need to do differently, if anything? The goal is to create one great story with our lives, worth sharing and celebrating every year.

Years ago, a friend let me participate in the ritual on Rosh Hashanah of dropping bread crumbs into a stream to release your sins from the previous year. I wrote a poem after that experience and gave it to her. Then I promptly forgot about the poem, though I still try to do the ritual every year. Recently, she mailed it to me. I’ll include an excerpt of it here as a kind of blessing–to thank her and you for this great story we are weaving together.

*****

The Days of Awe

These are the days of awe.

Lie back in summer’s last green grasses.

Listen.

Each cricket’s song is slower now,

the wind smells of ripe apples,

the soil devours rain

and coughs up stones.

Blackbirds rise up from the fields

Like mist off a pond.

Trees gain color and restraint overnight,

act like old ladies who

snap their purses shut

in anticipation of a need.

Remember

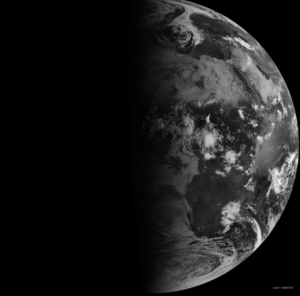

The sun isn’t travelling

East to West.

We are

spinning — West to East,

setting to rising,

beginnings growing out of endings,

not the other way around.

Lie back in the wet grass.

Wait for the sky to grow dark.

Breathe in the moon

like a question

you’re not quite ready to ask.

Be like the river

Who moves toward the unknown,

who doesn’t turn around

and ask the mountain for directions.

Listen to the grace of insects,

then drop, swell, and release

like bread in cool, swirling waters.

–SCR (9/26/99)

“Some pursue happiness, others create it”

“Some pursue happiness, others create it”